Crash Course: The Dewey Decimal System

- Erica Larsen

- Jun 20, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2025

I hear families coming into the kids’ section nearly every day excited to check out books about dinosaurs, the Titanic, or Minecraft, among other fascinating non-fiction subjects.... but sometimes those smiles dim as they approach our non-fiction shelves and find themselves confronted by books in a seemingly random order. Of course, I’ve gotten very good at answering the age-old question: “Where are your dinosaur books?”

Annoyingly, there isn’t a good short answer to give kids who ask that question, because the short answer is, “The dinosaur books are in the 567s,” and of course that raises a whole bunch of new questions: "Where are the 567s? What are the 567s? What about the 566s and 568s? What are all these numbers doing in a library? I don’t want to have to do math! I just want a T. Rex book!"

And when I hear those questions, I say… Let me introduce you to a fun little thing called the Dewey Decimal System.

It's a classification scheme which establishes an order for the placement of nonfiction books on library shelves. It was developed nearly a century and a half ago by Melvil Dewey, who at the time was working at the Amherst College library in Amherst, Massachusetts. Coincidentally, I did my undergrad about a mile and a half from there, but spent all three years unaware of all the library history that surrounded me in that town… I was really missing out. Check it out for me, if you're ever there?

Anyway, Dewey published his classification system in a pamphlet in 1876, back when that was how cool new ideas were shared. Imagine what he could have done with a TikTok account and a smartphone ring light! Over the next few decades his system caught on, and today it is the most widely-used library organization system in the world.

The basic premise of the Dewey Decimal System is that each book gets a number according to the discipline or field of study it falls into, and then libraries shelve books in that order for ease of browsing. There are ten classes, which determine the number in the hundreds’ place—so we have 000s, 100s, 200s, and so on to the 900s. Each class is divided into 10 divisions (so, the 100s, 110s, 120s...) and then the divisions are divided even further into sections (120, 121, 122 and so on). For further detail, a cataloger might add a decimal point and any amount of trailing numbers to clarify.

For example, we have a book about T. Rex in the kids’ section by Natalie Lunis, called A T. Rex Named Sue: Sue Hendrickson's Huge Discovery. Its call number—the combination of numbers, letters, and words on a sticker on its spine—is J 567.9129 LUNIS. At first that sounds like gibberish, right? Let me explain.

The J in this call number indicates that it is in our “juvenile” collection: it's a kids’ book. The inclusion of the author’s last name, LUNIS, helps to distinguish it from other books with the same subject, which might have the same Dewey number. And speaking of that numerical monstrosity, we can dissect 567.912 as follows:

500 Science

560 Fossils & Prehistoric Life

567 Fossil cold-blooded vertebrates

567.9 Reptilia

567.91 Dinosaurs, by family

567.912 Saurischia

567.9129 Tyrannosaurus

As you can see, the addition of decimal points allows us to get super specific about the subjects of books. This helps, for example, when a reader is looking for one particular book, but is open to reading other books about that subject as well. Someone might ask me for A T. Rex Named Sue, and if it’s not checked in, I can still show them where it would be shelved and many of the books near it will also be about dinosaurs.

“Okay, Erica,” I hear you saying now. “I get that the numbers are useful, and I kinda get the concept of how they work, but how do I know where to start finding books about trains? LEGO? The National Hockey League? Greek mythology?!”

There are a lot of gray areas and how a book is catalogued can be pretty subjective, so the catalog computer is a big help (as is your local librarian!). As a start, here are the disciplines / fields of study covered by each Dewey class. And because I can’t resist sharing my favorite books, I’m also going to recommend a book from each Dewey class.

Behold! Erica’s Crash Course: Dewey Decimal System reading list! (Unlike our Summer Reading Challenge, this challenge has no prize... but if you read them all, I will give you a crisp high five and my everlasting respect and appreciation.)

000s: Computer science, information, & general works

027.4794 ORLEAN: The Library Book by Susan Orlean

100s: Philosophy & psychology

J 155.433 ZELINGE: A Smart Girl's Guide to Liking Herself -- Even on the Bad Days by Laurie E. Zelinger

200s: Religion

J 201.3 WILLIAM: Amazing Immortals: A Guide to Gods and Goddesses Around the World by Dinah Williams

300s: Social Sciences

370.9 EWING: Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago's South Side by Eve L. Ewing

400s: Language

409 DOREN: Babel: Around the World in Twenty Languages by Gaston Dorren

500s: Science

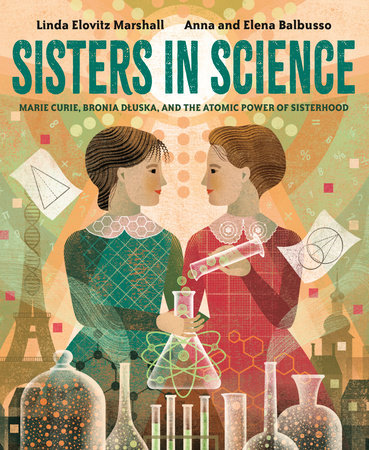

J 540.92 MARSHAL: Sisters in Science: Marie Curie, Bronia Dluska, and the Atomic Power of Sisterhood by Linda Elovitz Marshall

600s: Technology

636.8 SHAW: Cats of the World by Hannah Rene Shaw

700s: Arts & Recreation

794 EVANS: The World of Minecraft: A Visual History of the Global Phenomenon by Edwin Evans-Thirlwell

800s: Literature

814.6 GREEN: The Anthropocene Reviewed: Essays on a Human-Centered Planet by John Green

900s: History & Geography

J 940.5486 FLEMING: The Enigma Girls: How Ten Teenagers Broke Ciphers, Kept Secrets, and Helped Win World War II by Candace Fleming

Bonus!! 921: Biography

J 921 DEWEY ONEILL: The Efficient, Inventive (Often Annoying) Melvil Dewey by Alexis O’Neill